Common causes for tension in a software delivery team are poor understanding or alignment on what people should be doing and the standards we expect from our systems. This can lead to people working too hard or not enough, possibly due to working on unexpected things, to an unexpected quality bar. This post will explore the challenges faced by product delivery teams building and supporting software products that last over two years. I will show you how System Maturity Models and Competency Matrixes can provide support and alignment for managers, leaders and team members to create higher-performing teams with increased predictability.

Tensions

The software delivery world is a fast-paced and ever-evolving industry. New tools, techniques, and expectations seem to land on us every week. To move fast, we want to empower our people, provide high-trust environments, and unite our teams with a strong sense of belonging. But we often face headwinds when team members change, we have outages or incidents, or we miss deadlines. These headwinds can fuel growing tensions and conflict. It can be hard to know when to double down on some practices or to pivot and try something new. I find that there is a standard tension in software delivery teams between:

- Being fast vs. being reckless

- Providing autonomy vs. avoiding divergent execution

- United team vs. excessive Mob Programming and Swarming, leading to burnout

- Predictable vs. slow

We may see this in practice where you use a tool you are familiar with to get something done quickly, but it is different for the team. This local optimisation for yourself may slow the team down in the long term. In another example, the team may decide that turning off the tests will allow builds and deployments to be faster, but then we see an increase in deployment failures.

Common advice

Daniel Pink shows us in Drive that money has limited and sometimes detrimental effects on performance as a motivating mechanism. Instead, he shows that for creative and collaborative pursuits, Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose are far more effective motivators for long-term performance. David Marquet support’s the principle of these concepts in Turn the Ship Around by suggesting that we are more effective if we can push authority to the information instead of the information to authority. Blanchard’s Situational Leadership is an entire model based on how to empower our team members through delegation. On the surface, delegation is a popular, influential, and successful mechanism for team success. However, some caveats often get missed, especially in summaries of these books or from those who “read the first few chapters and got the point”.

Caveats

While the common takeaway from Drive is the catchcry “Autonomy, Mastery, Purpose”, the less common retort is “but not in that order”. In the first few chapters of Turn the Ship Around, the author shows that he gets higher levels of team buy-in with delegation, but later in the book, we find that it causes significant problems. Situational Leadership empowers people through delegation, but delegation is the fourth step in a progression.

If misinterpreted as “just delegate”, each model will cause issues. “Control without competency is chaos” from Turn the Ship Around helps us see that we should first define the purpose and then know what to master before finally providing space for autonomy. Situational Leadership shows us when to offer high levels of support and when to give space to avoid the “micro-manager vs. unsupported” balancing act.

Concerns

Software development teams can feel under-supported if they lack clarity on their roles and responsibilities. Often, we find team members compensating for other teammate’s deficiencies. This kind of assistance can be helpful in the short term, especially if it is explicit and requested. Over more extended periods, it can lead to confusion and resentment throughout the team. People want clarity on the responsibilities of their role and how they can move to a role with their desired responsibilities.

Teams can also be frustrated when they try to innovate but face friction or conflict, leading to disappointment. Team members may also feel frustrated when others in the team innovate in unexpected ways. The phrase “scrappy, not crappy” is unclear on exactly what would constitute crappy, and at what point does scrappy become gold-plated.

Confusion can also arise when we are unclear on the properties we expect in a system and to which quality bar these properties should be observed. For example, if a system should be fast, is 100ms response time good enough, or should it be 1ms? Is this for all requests or just at the p50 or p99? The system should be highly available, but how available? Is the appetite for 5 minutes of downtime per year (99.999%), or is it no downtime during the trading week, while downtime on non-trading hours is acceptable? Should we prioritise security, availability, adaptability, or performance right now?

Clarity on System Quality with a Maturity Model

First, we can get clarity on what we expect from our systems. Many teams without guidance will vary widely in their systems’ observed properties. These ad-hoc variations can lead to unpredictable behaviours in the systems or the people supporting the systems. This chaotic environment can leave team members feeling under-supported and confused. This confusion often leads to conflict within the team and across teams.

Why is predictability important? (The Power of Predictability – HBR)

If we can have higher levels of consistency in our systems, we not only “solve it once to solve it everywhere” but also enable higher levels of team mobility and low costs to create learning pathways. Once we achieve consistency, we can extract more value by systematising processes, tooling for rapid change management, and preparing for scale. Finally, once you have systematised these processes, you can look for high-leverage points to become Strategic Enablers.

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | |

| How it feels | Chaotic | Toil | Guided | Enabled |

| Behaviours & Actions | Communicate | Applying and remediating controls in a repeatable manner, but often manually | Focus on target work, as controls are systematised | Seeking Strategic Levers |

| Impact | Awareness | Consistency and governance | Speed through reduced rework and compliance interrupts | Increased Competitive Advantage |

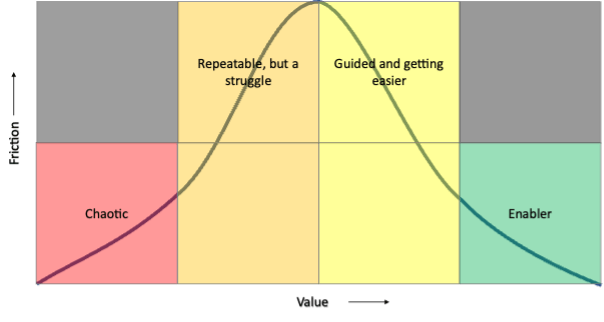

We should acknowledge that there is a non-zero cost to achieving this consistency. Moving through the phases of Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, and Ability takes time and energy. This transitional phase can be seen as high friction. Finding consistency through repeatable behaviours is often initially manual. The cost of consistency is the manual labour to either create the controls or meet the requirements of these controls, which can feel like toil. Once consistency levels have been achieved, these controls can be systematised through automation, ceremonies, or processes. When quality controls are systematised, it becomes easier to maintain and improve them, allowing the teams to restore focus back to the work and focus less on the controls. Finally, with the support of a guided and systematised set of quality controls, the team can now feel enabled and encouraged to find strategic levers to seek competitive advantage.

A metaphor for these controls – providing roads for cars:

- Chaotic – no roads

- Toil – creating roads, with lanes and lines

- Guided – Guard rails, road signs and maps

- Enabled – Driver Assist or even Autonomous cars

Each of these levels incrementally builds a capability.

For a software delivery system’s maturity model, I have found that using the initial categories of Plan it, Build it, Ship it, Run it, Protect it provides good guidance on the properties of your system to focus on. Each of these categories could be further reduced to subcategories.

We can look to prior art for guidance on maturities for each category for example DORA, Modern Software Engineering, STRIDE etc.

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | |

| Plan it | Outcomes are known | Outcomes are measurable | Outcomes are prioritised | Outcomes are aligned to business goals |

| Dependencies are known | Risks are known | Risks are managed | Outcomes, Risks and Dependencies drive long range strategy | |

| Work-in-progress is limited | Plans are reviewed and approved | Plan execution is reviewed | Plan for iterative delivery | |

| Build it | Coding standards are defined | Reference Implementation provided | Build target/tooling defined | Coding standards are enforced |

| Branch Protection | Test Driven | Semantic Versioning | Automated Release notes | |

| Ship it | Infrastructure standards are defined | Infrastructure is tagged | IaC (Infrastructure as Code) | Automated infra policy breach detection |

| Deployment process defined | Independent Provisioning, Deployments & Releases | Automated IaC and CI/CD | Feature Flags | |

| Monthly deployments | Weekly deployments | Daily deployments | On-demand deployments | |

| Change failure rate <50% | Change failure rate <25% | Change failure rate <10% | Change failure rate <5% | |

| Run it | Workload requirements are known | Workload requirements are met | Workloads scale elastically | Workload anomaly detection |

| Operational support requirements are known | Operational support is planned | Operational support is practiced | Other teams can provide operational support | |

| Operational metrics are known | Operational metrics are collected | Operational metrics are readily observable | Operational metric anomaly detection | |

| Protect it | Code & Infra Vulnerability detection automation | Threat-modelling with C4 and STRIDE | Threats are mitigated or raised as risks | Policy as Code |

| Least privilege access | Access is audited | Anomalous access detection | Pen testing | |

| Data classification policy is defined | Data classification is enforced | Data classification drives access controls | Data classification drives retention and breach response |

This is just an example of a maturity model and is different from what I currently use, which is private IP and not for public distribution. Also note that I currently use four models, one each for Product Engineering, Data Engineering, Site Reliability Engineering and Application Security Engineering. This example above is a single brief combining ideas from each.

How to use your System Maturity Model

There are three specific ways I use System Maturity Models: I request evidence of achievement, we work on one level at a time, and we all move together.

To provide evidence for behaviour achievement, colour-coding copies of the maturity model can provide broad visibility. Red means not done, orange means in progress, and green means complete. If green, then the text is hyperlinked to the evidence of the completion. That might be a link to a policy document, a coding standard, an automated workflow, or a dashboard. This is great for managers to get a quick visual overview of progress, for auditors to understand compliance and for a bit of inter-team competition if appropriate.

I strongly encourage people to simultaneously work on a single level to reduce confusion and over-optimising in one area. I encourage people to complete all level 1 outcomes before moving to level 2. I also encourage teams to assist their peer teams when they complete level 1. Helping other teams reach their level 1 targets helps the wider department achieve its goals and builds inter-team relations. This can turn what may be a competitive relationship into a collaborative one. This technique can also work at a larger scale of cross-department assistance. The “All move together” technique allows us to find gaps in our processes, understanding and controls. It also helps frame the team of teams as a cohesive unit that can work together and share. Finally, moving together can avoid a weak-link challenge, which can leave companies exposed in areas of incident response, security, and data controls.

Clarity on Roles with a Competency Matrix

As a member of a software delivery team, I am interested not only in the systems I work on but also in the teams I work in. I want to know how to work well in my team, be recognised for my work, and be rewarded. I want clarity about my role in my team, to know how I can grow in this role and how to grow into other roles.

This clarity may be hard to find when we are trying to balance the needs of the team member against that of the team and that of the larger organisation. Team members want autonomy, growth opportunities, and challenging work in a safe environment. Teams operate well with diverse thinking, accessible and relevant data, shared purpose and standard operating procedures. Organisations often seek predictability and transparency while balancing that with being profitable and innovative. These needs can be a challenging balancing act to find harmony when sometimes these needs seem to be pulling in opposite directions. Instead of seeing these as opposite ends on a spectrum, we can frame them as constraints of a more significant challenge.

A Competency Matrix is a similar tool to our Systems Maturity Model. It can provide the same level of guidance for what people should do in their roles. By clarifying what is expected for each progression in a role, we can give the individual and their teams support. People are clear on what they should be doing now and what they can do to grow into new roles. Teammates can also clearly understand what is expected of others, avoiding unnecessary conflict or missed opportunities. The Competency Matrix maps a set of behaviours to roles. Each cell clarifies both the expected demonstratable performance level of behaviour for a role and the scope within the organisation in which the behaviour is demonstrated. For example, you may have two roles that both need to do project planning. Where one may need to plan for a team of 5 for a 2-week sprint, another may need to plan for three teams for the quarter and ensure their plans align. While the skill set is the same, the scope at which the competency is demonstrated is different.

Using a similar matrix to the System’s Maturity Model, first, we can list the skills, abilities, and behaviours as row titles. Then, we can create column titles that represent our roles.

| Junior | Senior | Principal | |

| Plan it | Attends planning | Plans a team’s project | Guide multiple Seniors |

| Can identify business goals | Aligns plans with business goals | Ensures team’s plans are aligned | |

| Build it | Contributes to development | Accountable for the team’s software development | Defines development practices across teams |

| Can identify Tech Debt | Documents tech debt | Approves tech debt | |

| Ship it | Deploys code | Releases features | Defines Release process |

| Keeps build green | Keeps builds fast | Coaches CI/CD | |

| Run it | Can identify the team SLOs | Ensures team SLOs are measured | Defines SLOs for multiple teams |

| Attends Incident Response training | First responder for the team | Incident Commander for multiple teams | |

| Protect it | Contributes to patching vulnerable software | Creates and maintains Threat Models | Reviews and remediates threats. |

Focusing on a couple of example rows, we can see in the second row of competencies that a Junior is only expected to demonstrate knowledge of the business goals by identifying them.

A Senior is expected to create plans that align with the business goals. A Principal (in this made-up hierarchy) ensures that multiple teams’ plans and business goals are aligned.

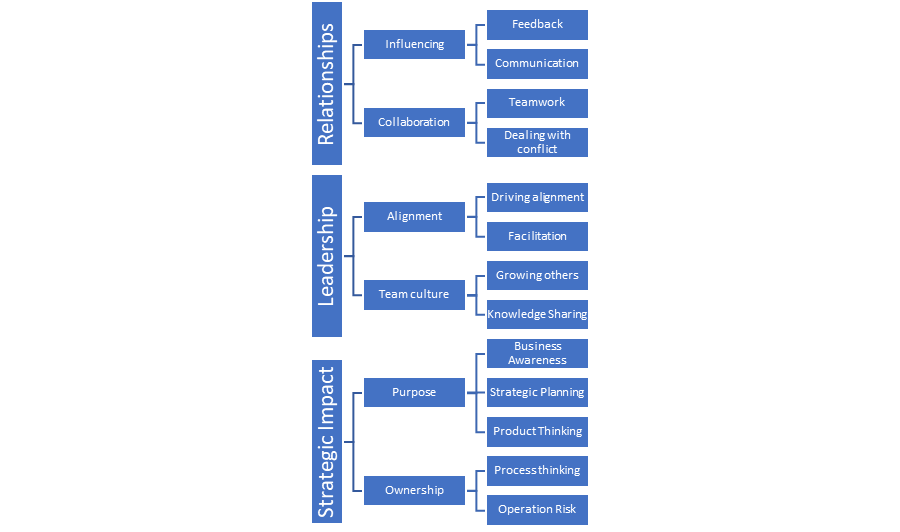

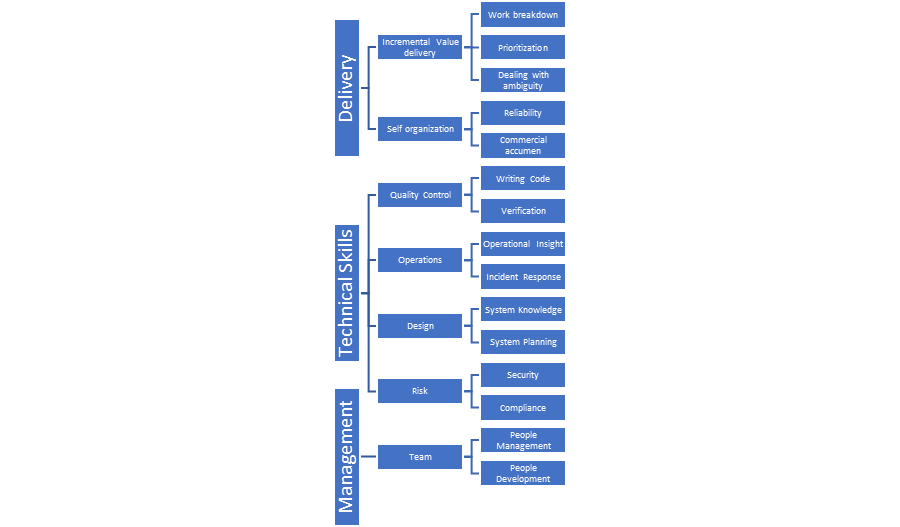

The Plan/Build/Ship/Run/Protect-it model creates focus areas that can quickly get you up and running to create your Competency Matrix. The CMM and SFIA models are alternatives, but I found them overwhelming. For a good balance of substance and clarity, I recommend the CircleCI Competency Matrix guidance, which shows why and how to write one. They also provide access to their own Creative Commons Licensed Competency Matrix. You will note that the Circle CI competency matrix has areas and sub-areas of focus. This breakdown allows people to narrow their focus without consuming the entire matrix. An alteration I found to be more effective was when we started with skills and behaviours that were the most common across roles and then finished with role-specific skills and behaviours. This had two benefits; firstly, it reminded our engineers that people skills are essential. It also meant that the top part of the Software Engineering Competency Matrix was reusable for other disciplines like SRE, product management and sales or marketing. Leading with Relationships and Leadership frames a culture where people are important, and everyone is a leader, even in a role with minimal authority or people management responsibilities. Following up with Strategic Impact reminds people that our roles fit a larger picture.

We then move to increasingly specific behaviours, skills and abilities. Fewer roles in the organisation will have a delivery focus, and fewer still have the technical skill demands of a Product Software Engineer.

Conclusion

In conclusion, System Maturity Models and Competency Matrixes can provide valuable support and alignment for product delivery teams building and supporting software products. These tools can help managers, leaders, and team members create higher-performing teams with increased predictability. By addressing common causes of tension in software delivery teams, such as poor understanding or alignment on roles and responsibilities, competing priorities, and unclear quality standards, these models can help teams stay focused on their goals and work together more effectively. Ultimately, by promoting autonomy, mastery, and purpose, and by providing clear guidance on roles and responsibilities, System Maturity Models and Competency Matrixes can help software delivery teams achieve long-term success.

References:

- Daniel Pink’s book – Drive

- L. David Marquet’s book – Turn the Ship Around

- Ken Blanchard’s leadership technique and training – SLII Training: A Situational Approach to Leadership

- Latency Percentiles are Incorrect P99 of the Times | Last9

- If P99 Latency is BS, What’s the Alternative? – P99 CONF

- The Prosci ADKAR® Model | Prosci

- Google Site Reliability Engineering – Chapter 5 Eliminating Toil

- McChrystal et.al book – Team of Teams

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capability_Maturity_Model

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capability_Immaturity_Model

- https://sfia-online.org/en/sfia-8

- https://circleci.com/blog/why-we-re-designed-our-engineering-career-paths-at-circleci/